My seventeen year old slept overnight at school last night with a group of forty other senior school girls in a gesture of solidarity with the homeless. It was intended as a fund raiser but my daughter is a little sceptical about the value of such exercises when it comes to making a real difference to homelessness.

‘Better to join a soup kitchen,’ her boyfriend had suggested. I’m inclined to agree.

I bought my daughter a padded mat from Kathmandu to avoid sleeping on the bricks of the school’s breezeway and despite the fact that such a ‘mattress’ does not exactly emulate the plight of the homeless my daughter agreed to use it.

Now we have to figure out how to deflate this amazing piece of padding. It is self inflating and operates by opening and closing the nozzle. Every time I open the nozzle though I cannot be sure whether it is inflating or deflating.

Perhaps, as my husband says, we should read the instructions first.

I tend to by pass written instructions. I like to figure out things for myself and invariably as with this inflatable self inflating sleeping bag I find myself in trouble.

It’s a type of laziness I expect, the voice within that says 'let me at it'. I can figure it out, only to be stymied at the first obstacle.

I have been reading about shame these last few weeks, shame and the way it links to grief and death. Jeffrey Kauffman's series of essays on The shame of Death grief and trauma I had never thought of shame like this before, I had never considered that the essence of shame lies in our bodies and our vulnerabilities and how difficult we find it to accept the limitations of our bodies, especially when it comes to illness and death.

Perhaps this is one of the reasons why I hesitate to go through the process of having a colonoscopy. I even shudder to write the word. I expect you all know the procedure.

For some reason that I cannot fathom I have always held a morbid fear of getting bowel cancer. There is no history of bowel cancer in my family, not as far as I know.

I’m not sure how to put this. I wonder whether it has to do with that part of the body, the hidden part that ends in the anus and is so closely related to the toilet. I suspect part of my fear and my deep shame goes back to some childhood anxiety about bottoms and poos and all those secret bits of bodies that go on underneath.

When I was little I imagined that my soul which was meant to stay pure and white was located in my bottom close to my poo hole. I do not know where this idea came from but it has long stayed with me. The idea that centre of my soul on which all sins were marked as dark stains was located so close to the dirtiest part of me.

Maybe my adult fear of bowel cancer harks back to this. And perhaps for this reason I have long resisted the idea that I should endure a colonoscopy if only as a screening procedure to rule out any polyps or precancerous cells.

Shame and the body. If I put those two things together, the first thing I think about is the shame of shitting, then I think of the shame of sex and then I think of the shame of illness generally and finally I think of the shame of dirt, as in a dirty house and of getting things wrong in areas where I think I should get them right.

I’m not too ashamed of being unable to deflate the Kathmandu bed mat. I don’t expect that of myself, but there are areas where I do expect more of myself and it is in these areas where I suffer the most.

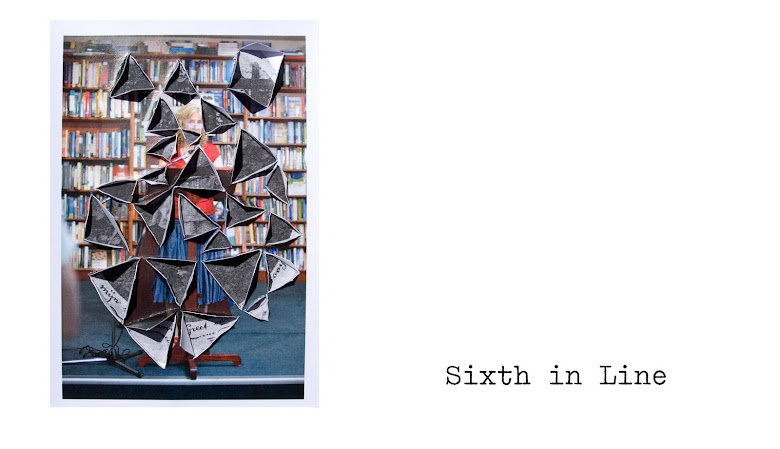

In an effort to break up the text and to illustrate some aspect of my earlier shame I include a picture here from my childhood, one that demonstrates the clutter in which we once lived. I'm the headless one on the bed.

And in this photo, I'm the one on the left with long fair hair. The girl facing the camera was a visitor. The other two are siblings. In black and white the room may not look quite so bad as I once imagined, the mess and the clutter that is, but in my memory it is.

And did you know that shame and pride are close cousins? Pride to cover over our shame. I think often about my mother’s pride and how much I have soaked it in.

These days I sit with my mother in her retirement village room and listen yet again as she boasts about her age.

‘I’m 91 years old. I don’t get sick, It’s amazing. Other people here, all the other people here are coughing and spluttering. So many have the flu, but me not a sniffle.’

‘That’s good’ I say. ‘But if you get so much as a sniffle, or a tickle in your throat you must tell the doctor straight away.’

It feels like a threat. My mother towards the end of her life refuses to recognise the possibility of her death any day now, and I’m not far behind reluctant to acknowledge the same about my own.

In my family we boast about our good health, our genes, our immunity.

I spread the sorbolene cream over my mother’s legs and pull back once again at the stale smell that wafts over me whenever I take off her slippers. They are all she wears on her feet these days, special slippers, with Velcro strips that adhere together to make for easy wearing. She cannot otherwise get her slippers on and off. They smell of the vinegar of old age and dead skin.

She knows it, I suspect. My mother knows that her feet let off this sad stale smell but she says nothing.

I say nothing but spread the white smooth cream up and down her ankles and calves as if they are my own.

There’s a dark spot like a blood blister that I had not noticed before. I rub it with the tip of my finger. It’s smooth to touch.

‘I noticed that too, my mother says. It wasn’t there before.’

‘The mark of death,’ I want to say. ‘Your skin is breaking down.’

But no. ‘It’s probably just a blood blister,’ I say. ‘I get them all the time, ever since I had babies.’

‘Nothing to worry about then,’ my mother says.

‘Maybe mention it to the doctor next time you see him.’

All this emphasis on our bodies. All this effort to reduce our skin and bones into efficient machines that might go on forever, if only to keep out the cold and the shame.

Showing posts with label homelessness. Show all posts

Showing posts with label homelessness. Show all posts

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Saturday, March 12, 2011

A yellow towel

I sit beside my mother on the blue Ventura bus. It snakes its way through the back streets of Box Hill. We have been travelling for nearly an hour. Already the trip is long, from Mentone beach into Surrey Hills. We did not have time to think or to decide on the clothes we might wear, or the books we might bring to read on this long journey. We could not stay a minute longer.

It happens like this. On Friday nights my father drinks himself into a stupor. Most times he falls asleep on his chair in front of the television. He leaves us in peace, but sometimes the drinking starts earlier before Friday. It might begin on a Wednesday. On days like these, my father does not go to work. Instead he drinks and sleeps, sleeps and drinks, and in between times he looks to us for company and for fights.

He looks especially to my mother, but she pretends she does not notice him and the more she pretends the more angry he becomes until in an explosion of rage he throws a radiator at her, as he did this morning, or he rips off her dress, as he did last week, or he tears out her hair.

Last week we left to stay with my big brother and his new wife in Hawthorn but we have overstayed our welcome there. This week we visit a friend of my mother’s who has said that my mother and the two little ones can stay the night with her, but we older ones will need to fend for ourselves.

And so it was decided. We older ones will catch the blue bus back to our home, but we will not go inside. We will sleep in the garage if we are brave enough to sneak into the backyard and otherwise we will fend for ourselves in the outside world.

The bus drops us off two stops before our house. We do not want our father to see us from his front seat in the lounge room. We walk around the block and approach our house from behind. Even from behind, our house does not feel safe. There is a vacant block behind the grey paling fence that divides the back of our house off from the next as yet unbuilt property. We will spend the night there.

My brothers climb the fence and sneak into the back yard to collect three towels off the washing line. We left them there the day before, after we had been swimming. We will use the towels as blankets.

Mine is a yellow towel. It is summertime. A hot night. I do not need a blanket. I use the towel as a mattress, a thin mattress that cannot cushion me from the rocks and rough bits that stick into my body every time I try to turn over in my sleep, but it is a comfort nevertheless. The two boys offer the towels to us three girls as an act of gallantry. They are strong boys. They can do without.

I look at the stars and imagine myself far away even as I marvel at the idea of my twelve-year-old self as this homeless person. How they would marvel at my school. How shocked they would be. Families from my school do not sleep out of doors at night because their father is drunk.

The next morning we go to Mass. The priest in white and gold vestments raises the host to the altar in the Hosanna chorus and I look down at my dirty fingernails, dirtier than usual for all the grit of my stony dirt bed the night before and I marvel at the way life can seem so very different from the outside.

It happens like this. On Friday nights my father drinks himself into a stupor. Most times he falls asleep on his chair in front of the television. He leaves us in peace, but sometimes the drinking starts earlier before Friday. It might begin on a Wednesday. On days like these, my father does not go to work. Instead he drinks and sleeps, sleeps and drinks, and in between times he looks to us for company and for fights.

He looks especially to my mother, but she pretends she does not notice him and the more she pretends the more angry he becomes until in an explosion of rage he throws a radiator at her, as he did this morning, or he rips off her dress, as he did last week, or he tears out her hair.

Last week we left to stay with my big brother and his new wife in Hawthorn but we have overstayed our welcome there. This week we visit a friend of my mother’s who has said that my mother and the two little ones can stay the night with her, but we older ones will need to fend for ourselves.

And so it was decided. We older ones will catch the blue bus back to our home, but we will not go inside. We will sleep in the garage if we are brave enough to sneak into the backyard and otherwise we will fend for ourselves in the outside world.

The bus drops us off two stops before our house. We do not want our father to see us from his front seat in the lounge room. We walk around the block and approach our house from behind. Even from behind, our house does not feel safe. There is a vacant block behind the grey paling fence that divides the back of our house off from the next as yet unbuilt property. We will spend the night there.

My brothers climb the fence and sneak into the back yard to collect three towels off the washing line. We left them there the day before, after we had been swimming. We will use the towels as blankets.

Mine is a yellow towel. It is summertime. A hot night. I do not need a blanket. I use the towel as a mattress, a thin mattress that cannot cushion me from the rocks and rough bits that stick into my body every time I try to turn over in my sleep, but it is a comfort nevertheless. The two boys offer the towels to us three girls as an act of gallantry. They are strong boys. They can do without.

I look at the stars and imagine myself far away even as I marvel at the idea of my twelve-year-old self as this homeless person. How they would marvel at my school. How shocked they would be. Families from my school do not sleep out of doors at night because their father is drunk.

The next morning we go to Mass. The priest in white and gold vestments raises the host to the altar in the Hosanna chorus and I look down at my dirty fingernails, dirtier than usual for all the grit of my stony dirt bed the night before and I marvel at the way life can seem so very different from the outside.

Saturday, March 13, 2010

The Geography of Home

I break all the rules and write too much, so my apologies in advance. This post derived from Niamh's geographical meme at Various. I read her post and then Dominic's. Then I took off on my own. Later I read Rachel's.

I see now that I have failed on all accounts to answer the questions Niamh set. I was never good at geography, maths or comprehension. In my defense, I am an autobiographical writer. I cannot bear simply to list things or to answer direct questions. I like to color them in as well.

Geographical Meme

Geography was a subject I took at school as an obligation rather than a pleasure. I did it out of necessity. Learning about the landscape and the people who occupied that landscape failed to excite me. I spent my childhood in a fog of not belonging. I thought that I should have been born elsewhere.

I thought I belonged in Europe but here I was in Australia with all these children at primary school whose connection to their land seemed certain and unquestionable. My own connection seemed tenuous.

I was born in Diamond Valley Community Hospital in Diamond Creek and spent my first three years in the nearby suburb of Greensborough, first in a converted chook shed that my parents used to occupy their then six children and later in a weatherboard house my father had built himself in Henry Street. In those days Greensborough was a place of grassy paddocks and dusty roads. A suburban countryside.

I spent my fourth year of life in the mountain suburb of Healesville on Myers Creek Road, where my father and my uncle, my mother’s brother and his wife had gone into business. They had bought a series of small huts as accommodation for city visitors and a café-cum-milkbar. The venture failed. After a year we moved into rental accommodation in Wentworth Avenue in the genteel suburb of Canterbury, or Camberwell as it is most commonly known. Ours was the scruffiest house in an otherwise beautifully manicured street.

These are the years of my childhood I remember best, my years in that rundown Edwardian gentleman’s residence when all us kids were still at home, though my older brothers left home during this time. When I was fourteen we moved to a new AV Jennings special in Cheltenham, which my parents managed to buy.

When I was fifteen my oldest brother decided that my parents should sort out their mess – primarily my father’s alcoholism – and he organised to have the six youngest move out of home. My sister and I stayed with a Dutch foster family back in Camberwell but the arrangement broke down and we wound up boarding at our convent school, Vaucluse, in Richmond, for the rest of that year. We then moved back ‘home’ to Cheltenham for my sixteenth year.

By the time I turned seventeen, life at home had become untenable again and so the second oldest brother organised for my mother to rent a shabby cottage near the sea in Parkdale. This time she left my father and we four youngest lived with her. We were visited at times by another older brother who stayed with us when he could not sort out his bed sitter accommodation, and by my older sister who was herself homeless for a time, for all sorts of complicated reasons.

I finished my last year of school in Parkdale when we moved back to Cheltenham on the basis of a miracle. My mother swore that my father was reformed and would never drink again. His reformation lasted little over a month, as I recall, and by the end of the Christmas holidays when I had started at university my father was back to his worst. My younger sister, the one immediately below me, went back to boarding school, in order to survive her final year and my mother lived at home in Cheltenham with me and my youngest sister, brother and our fast deteriorating father.

At the end of that first year at university which passes through my mind in a haze of misery, I moved into an old half house with my younger sister who had by now finished her schooling and was off to university herself and her girlfriend from school. An unstable threesome, we lived in Caulfield, first in the run-down half house in Royal Parade near the then Chisholm College and later in an upstairs flat still in Caulfield not far from the race course on the corner of Grange Road and the Princes highway.

Several further moves followed.

I will list them here: Leila Street in Ormond with my first boyfriend to Beach Road in Black Rock in a dilapidated half house by the sea, again with my first boyfriend, and then onto Westbury Street East St Kilda, the year I started my first job as a social worker, at first with my first boyfriend but in the end alone briefly after we broke up. Then I moved back to Caulfield and shared yet another flat, this time with my youngest sister for a year, after which she got married and I moved in with the man who in time became my husband in a group house in Fermanagh Road in Camberwell. I shared with him and the three other occupants of that half house for only a few months before my then partner soon to become my husband and I moved to Canberra. The government had seconded him into the Department of Administrative Services and we stayed in Northbourne Avenue in the city for some six months.

Eventually we returned to Melbourne and rented a small old fashioned apartment in a block of four in Bourke Road Camberwell, from where we were married and later, forced to leave when the block was sold, we moved into a small single standing unit in Auburn Road. We lived there for about a year before we bought the house in which we now live and have been living these past 30 years.

My early days were days of constant movement but since 1980 I have lived in the same place. In many ways I can see myself living here for some time longer beyond the time our youngest daughter leaves home into old age, by which time we will no doubt move again if death does not take us first.

All up I calculate that I have moved house twenty times and all of these bar one within the first twenty-seven years of my life. For the past thirty years I have lived in the one place, in Hawthorn, an inner city suburb of Melbourne, on a busy main road surrounded by genteel and quiet streets.

I have only lived outside of the state of Victoria of which Melbourne is its capital city once for six months when we moved to Canberra and I hated it. I resolved then that I would spend the rest of my life in the city in which I was born.

Having spent my entire childhood in the belief I should live elsewhere in Europe – go back to my mother’s home in Holland – I finally decided that I wanted to stay put. I am a homebody – nomadic only in mind. Apart from brief trips overseas and interstate I maintain my links to the land and space here. My home.

I see now that I have failed on all accounts to answer the questions Niamh set. I was never good at geography, maths or comprehension. In my defense, I am an autobiographical writer. I cannot bear simply to list things or to answer direct questions. I like to color them in as well.

Geographical Meme

Geography was a subject I took at school as an obligation rather than a pleasure. I did it out of necessity. Learning about the landscape and the people who occupied that landscape failed to excite me. I spent my childhood in a fog of not belonging. I thought that I should have been born elsewhere.

I thought I belonged in Europe but here I was in Australia with all these children at primary school whose connection to their land seemed certain and unquestionable. My own connection seemed tenuous.

I was born in Diamond Valley Community Hospital in Diamond Creek and spent my first three years in the nearby suburb of Greensborough, first in a converted chook shed that my parents used to occupy their then six children and later in a weatherboard house my father had built himself in Henry Street. In those days Greensborough was a place of grassy paddocks and dusty roads. A suburban countryside.

I spent my fourth year of life in the mountain suburb of Healesville on Myers Creek Road, where my father and my uncle, my mother’s brother and his wife had gone into business. They had bought a series of small huts as accommodation for city visitors and a café-cum-milkbar. The venture failed. After a year we moved into rental accommodation in Wentworth Avenue in the genteel suburb of Canterbury, or Camberwell as it is most commonly known. Ours was the scruffiest house in an otherwise beautifully manicured street.

These are the years of my childhood I remember best, my years in that rundown Edwardian gentleman’s residence when all us kids were still at home, though my older brothers left home during this time. When I was fourteen we moved to a new AV Jennings special in Cheltenham, which my parents managed to buy.

When I was fifteen my oldest brother decided that my parents should sort out their mess – primarily my father’s alcoholism – and he organised to have the six youngest move out of home. My sister and I stayed with a Dutch foster family back in Camberwell but the arrangement broke down and we wound up boarding at our convent school, Vaucluse, in Richmond, for the rest of that year. We then moved back ‘home’ to Cheltenham for my sixteenth year.

By the time I turned seventeen, life at home had become untenable again and so the second oldest brother organised for my mother to rent a shabby cottage near the sea in Parkdale. This time she left my father and we four youngest lived with her. We were visited at times by another older brother who stayed with us when he could not sort out his bed sitter accommodation, and by my older sister who was herself homeless for a time, for all sorts of complicated reasons.

I finished my last year of school in Parkdale when we moved back to Cheltenham on the basis of a miracle. My mother swore that my father was reformed and would never drink again. His reformation lasted little over a month, as I recall, and by the end of the Christmas holidays when I had started at university my father was back to his worst. My younger sister, the one immediately below me, went back to boarding school, in order to survive her final year and my mother lived at home in Cheltenham with me and my youngest sister, brother and our fast deteriorating father.

At the end of that first year at university which passes through my mind in a haze of misery, I moved into an old half house with my younger sister who had by now finished her schooling and was off to university herself and her girlfriend from school. An unstable threesome, we lived in Caulfield, first in the run-down half house in Royal Parade near the then Chisholm College and later in an upstairs flat still in Caulfield not far from the race course on the corner of Grange Road and the Princes highway.

Several further moves followed.

I will list them here: Leila Street in Ormond with my first boyfriend to Beach Road in Black Rock in a dilapidated half house by the sea, again with my first boyfriend, and then onto Westbury Street East St Kilda, the year I started my first job as a social worker, at first with my first boyfriend but in the end alone briefly after we broke up. Then I moved back to Caulfield and shared yet another flat, this time with my youngest sister for a year, after which she got married and I moved in with the man who in time became my husband in a group house in Fermanagh Road in Camberwell. I shared with him and the three other occupants of that half house for only a few months before my then partner soon to become my husband and I moved to Canberra. The government had seconded him into the Department of Administrative Services and we stayed in Northbourne Avenue in the city for some six months.

Eventually we returned to Melbourne and rented a small old fashioned apartment in a block of four in Bourke Road Camberwell, from where we were married and later, forced to leave when the block was sold, we moved into a small single standing unit in Auburn Road. We lived there for about a year before we bought the house in which we now live and have been living these past 30 years.

My early days were days of constant movement but since 1980 I have lived in the same place. In many ways I can see myself living here for some time longer beyond the time our youngest daughter leaves home into old age, by which time we will no doubt move again if death does not take us first.

All up I calculate that I have moved house twenty times and all of these bar one within the first twenty-seven years of my life. For the past thirty years I have lived in the one place, in Hawthorn, an inner city suburb of Melbourne, on a busy main road surrounded by genteel and quiet streets.

I have only lived outside of the state of Victoria of which Melbourne is its capital city once for six months when we moved to Canberra and I hated it. I resolved then that I would spend the rest of my life in the city in which I was born.

Having spent my entire childhood in the belief I should live elsewhere in Europe – go back to my mother’s home in Holland – I finally decided that I wanted to stay put. I am a homebody – nomadic only in mind. Apart from brief trips overseas and interstate I maintain my links to the land and space here. My home.

Labels:

geography,

home,

homelessness,

leaving home,

nomadic styles,

settlement

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)