There’s a note written on the back of an envelope on my desk

this morning. I remember it now. I

wrote it in the middle of the night after waking from a dream. I have little inkling of the dream,

though once I consult the note on the envelope all might be revealed.

Yesterday I went with my mother to visit her

cardiologist. Her heart seems fine

at the moment, blood pressure 125 over 70, better then mine. That one leaky valve seems to have

stopped leaking. Her heart is

smaller and functioning well with the aid of medication.

I mentioned to the cardiologist that my mother had lost her

sister recently and he listened patiently as my mother went over the story

again, about how she had not expected her sister who was six years younger to

die; how it is so much harder when her sister is so far away in Holland; how

she could not even go to the funeral.

I’ve been distracted by a phone call from a colleague asking

questions about another colleague and suddenly I feel I am dragged into the

mire of politics, which is perhaps similar to the issue of sibling rivalry and

all the ugly emotions that get stirred up when families and professions are in

conflict.

Enough said, back to my mother. Earlier in the waiting room as we waited for the

cardiologist to materialise my mother mentioned the fact that tomorrow is

Mother’s Day.

I have reservations about this day. It stirs up mixed feelings.

‘I’m not interested in Mother’s day,’ my mother said, as if

she had read my mind, 'but your brother, F, came during the week with a huge

bunch of flowers.'

My aversion to Mother’s Day must have started long ago when

I was young. My mother told us

repeatedly then how she was not interested in Mother’s Day. It was a commercial ploy to get people

to send money, she said.

I’ve tended

to agree. On Mother’s Day we feel

obliged to honour our mothers whether we want to or not.

And for me, even if I wanted to acknowledge my debt to my

mother on Mothers Day and my love for her, it would be marred by the fact that

the opportunity arrives on this one particular day of the year when someone

else dictates that I should honour my mother.

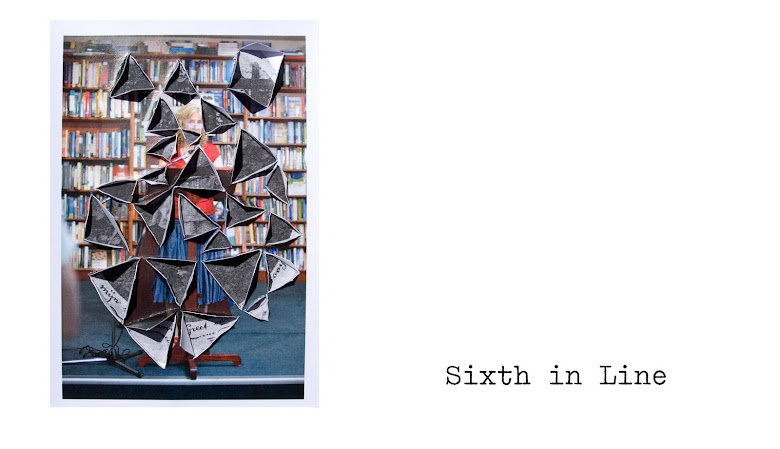

My mother with one of her babies. I've yet to ask if she recognises this one. It could be me. For years I've been on the hunt for a baby photo of me. It's not easy. This photo is poorly focussed and given my mother has had so many children, she must identify each by extraneous variables - the location of the photo, the dress she's wearing, the time of year.

I have tried to urge my children not to feel obliged

on Mothers Day.

It was easy when they were little. Their school might have orchestrated a card or a stall and a

small gift, but thereafter the day was as any other.

As our children grew older and could make up their own

minds, they were less inclined to make a fuss in much the way I have not fussed

in relation to my own mother.

My mother has urged us not to bother on Mother's Day and yet underneath I sense her desire that we do so.

Do I want my children to acknowledge me on this special

day? I’m not sure.

The same applies to Father’s Day. These are days of ritual and perhaps they go further than

mere commercialism. They stir up

feelings of ambivalence in some. For others they might become a way of

fulfilling obligations, that one day of the year event. After that it seems we need not acknowledge our

mothers at all.

It is the seemingly compulsory nature of Mothers Day that

troubles me.

And as for the dream: I went into the ‘exterocet’ by clicking on to an arrow that led to the

other side of a blog. In my dream

the exterocet was Internet speak for white space. Terrifying white space. No one had been there yet. It was the equivalent of hell.

On the surface, this snippet of dream makes little sense, but

there’s meaning there, if only I can unpick it.

.jpg)